Curriculum development and implementation

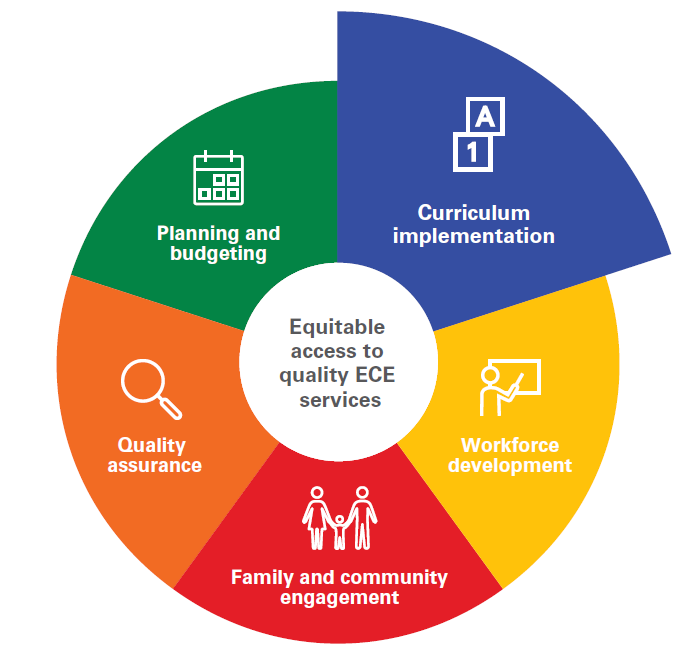

Core Function 2 focuses on ensuring that all children across early learning settings benefit from a developmentally and culturally appropriate curriculum and have access to learning and play materials that stimulate their development.

Core Function 2

ECE curriculum frameworks should ensure a “play-based learning” approach and that children are equipped with holistic skills, encompassing both foundational literacy and numeracy skills as well as broader socioemotional, creative, and physical skills, that will prepare them to successfully engage in primary education.

There is also a need to strengthen linkages between pre-primary and primary education settings and services, so that children are “school ready” and can transition smoothly to primary school. The extent to which curriculum goals between pre-primary education and primary education align in national policies will influence how children experience this transition (source).

Curriculum implementation is most commonly monitored as part of the monitoring of ECE staff, and thus closely related to workforce development, and in turn, quality assurance. Not only does this include assessing staff’s pedagogical practices and approaches in interpreting curricula, but this also includes the capacity to adapt this curricula to children’s specific needs as well as the everyday reality of the local context.

When it comes to implementing a pre-primary curriculum, some key considerations are that:

- Curriculum implementation is more likely to be effective if there are clear policy directives from appropriate institutions to ensure that roles and responsibilities are defined and that they align with the established governance structures [link to appropriate tool here]

- Appropriate technical capacity should be built across the sub-sectors not just for teachers, but also for other personnel who may need to understand the curriculum content, such as administrators and parents

- Tailored and localized approaches to curriculum implementation need to take place across the board, including in remote or impoverished locations

- User-friendly and practical implementation tools need to be developed, such as a teachers’ guide, student books, and guides for making and developing locally-made play materials

- Strong linkages need to be made with in-service and preservice teacher training

- The monitoring and evaluation and review mechanisms need to be take place regularly

Cross-cutting considerations

In situations of crisis and forced displacement, the ECE curriculum should be developed in a way that is flexible and adaptable to the needs and resources of the impacted community and need to be especially considerate of conflict sensitivity and flexible implementation approaches. It is especially crucial that ECE curricula address the psychosocial as well as social-emotional learning (SEL) needs and child well-being aspects related to health and nutritional neeeds of young children. Play-based curricula are especially valuable approaches here as they enhance the coping strategies of young children and help restore a sense of normalcy to everyday life. An example of this are the videos in Sesame Workshop’s Watch, Play, Learn video library, which are designed to bring playful early learning opportunities to children everywhere, with a focus on the unique needs and experiences of children affected by crises.

Transitional early learning programmes, such as accelerated, bridging, and remedial programmes, may offer an alternative pathway to prepare children who have missed the opportunity to attend a pre-primary programme before primary school. Such programmes can be designed rapidly through strategic partnerships and implemented at low-cost to produce positive impacts on children’s school readiness.

- Case study: Bangladesh - BRAC Humanitarian Play Lab: When playing becomes healing. This case study highlights BRAC’s Humanitarian Play Lab model in Bangladesh, which works with children and their families from myanmar’s Rohinga community who are displaced in Bangladesh. The Humanitarian Play Lab model is a contextualized adaptation of the BRAC Play Lab model and promotes healing through culturally rooted play.

- Case study: Ethiopia - Accelerated School Readiness Programme. This case study discusses the Accelerated School Readiness (ASR) Programme in Ethiopia, which was intended to improve the equity of access to pre-primary education for children in disadvantaged areas.

Pre-primary education has the potential to tackle gender inequalities by influencing gender socialization processes and addressing gender stereotypes and harmful gender norms at the stage when these identities are taking shape in young boys and girls. This can significantly contribute in preventing harmful social norms and stereotypes from occurring in the first place.

There is an urgent need to incorporate gender-responsiveness proactively and explicitly into the design and implementation of pre-primary programmes and to promote gender-transformative strategies with a system-wide perspective. Such programming is essential to creating equal futures from the early years. Curriculum development goes back to GRP4ECE in addressing the hidden curriculum and assessing materials and curriculum for gender bias and stereotypes. Classroom materials also need to address this, such as in the expansion of contextually relevant books and resources, including digital resources, for young girls and boys, and their teachers to reflect diverse roles and challenge gender stereotypes and harmful gender norms.

Example: Vietnam: Gender-responsive teaching and learning in the early years (GENTLE). This project, led by VVOB, focused on developing the capacity of preschool teachers and school leaders in fifteen districts in central Vietnam to challenge social and gender norms, create new rules, and support children in adopting new, more equitable attitudes and behaviors. Teachers and school leaders were provided with tools to effectively implement gender-responsive play-based learning at school and to advocate for this project at home with the parents of their young learners.

An inclusive approach relies on differentiated practices and it is necessary to rely on a wide range of expertise due to the diversity of children’s needs. Inclusive settings may require education, material, or environmental adaptations or modifications to maximize the participation of children who require more support, as well as individualized and specialized interventions. Curriculum and teaching and learning resources for young children should be reviewed to support inclusive education.

Recognizing the different needs of every child means recognizing that the means and methods to support learning vary. Approaches such as Universal Design for Learning, Multi-Tiered Systems of Support, and inclusive pedagogy highlight the need for differential learning support practices. The focus here is not on what distinguishes children, but rather on a continuum of strategies and intensity of support to meet all developmental needs. Additionally, assessments can also be adapted to be accessible to all learners.

Digital learning and educational technology

While the amount of time that young children spend with media and technology at home is continuing to increase, less is known about the types of digital learning experiences children have in early childhood education settings, and there is little extant research on how and in what contexts preschool teachers use technology and media in the classroom (Dore & Dynia, 2020).

With apps, digital books, games, video chatting software, and other interactive technologies that can be used with young children, as well as emerging new technologies, there are a plethora of options that caregivers and teachers have when using technology with early learners.

Digital learning approaches and educational technology may be used in positive ways that can enhance learning, notably when they are used to support learning goals and when their use involves co-viewing and co-participation between adults and children (NAEYC, n.d.). Some important considerations when it comes to looking at children’s digital media use and educational technology vis-a-vis curriculum considerations include the following:

Generally, when children actively engage with screens and content presented, greater benefits are realized as opposed to when they passively watch what is in front of them. Digital technology can add value to children’s learning, especially when used in ways that increase access to high-quality content and encourage peer interaction. More research needs to be conducted to determine how adults are actually using digital media modalities with children, in order to have a better understanding of both adults’ and children’s engagement.

Active co-viewing, or when adults watch television programming with children and engage in conversation around the content, can change a passive viewing experience into an interactive one. By engaging the child in conversation, adults can turn the viewing experience into an opportunity for reciprocal interactions with their child. Research around active co-viewing has shown direct and indirect benefits for both children and their caregivers, such as increased learning during watching, although the extent of cognitive outcomes is unknown. Further, it may be the act of spending quality time together with adults that is important, with co-viewing providing opportunities for adult scaffolding, that contributes to such benefits rather than the act of watching television itself (Gottschalk, 2019).

The quality of such digital learning approaches and technology is important as well. The case is often made that digital learning and technology, whatever form it takes, needs to be of “high quality” , but operationalizing what this means and what this looks like is often still under discussion. As a starting point, UNICEF has developed a set of criteria for selecting “world class” digital learning solutions: they should be interactive, adaptive, inclusive, market-relevant, playful, and nimble. However, it cannot be stressed enough that digital media and technology are learning tools and how they are used and implemented is equally important for impact.

Example: Selected examples of effective classroom practice involving technology tools and interactive media - preschoolers and kindergartners (NAEYC, 2012). Examples are provided of how technology and interactive media may be employed in a classroom setting.